The Growth of LTAD Models

The Long-Term Athlete Development (LTAD) model is a framework for an optimal training, competition and recovery schedule for each stage of athletic development. (Bayli et al., 2015)

The most important thing that LTAD models bring is individualised context to a person’s athletic development, and within that context it involves a host of variables that need to be understood by the practitioner, coach and multi-discipline team (MDT).

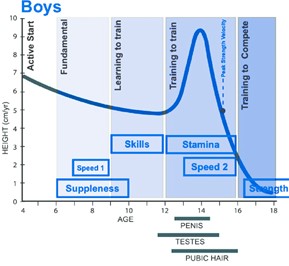

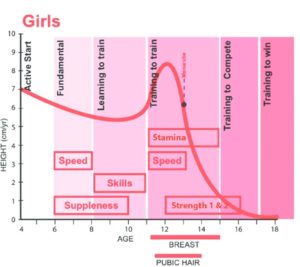

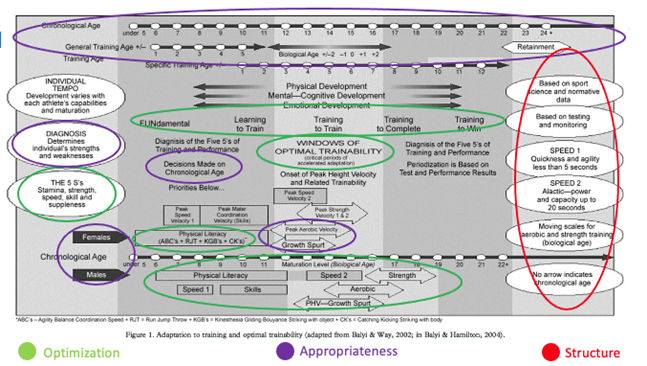

Over the last two decades or so, LTAD models have grown in number and popularity within the sports world. Ericsson’s 1993 paper, “The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance”, demonstrated that a decade of deliberate practice was the cornerstone of expert performance, which brought about the 10,000-hour rule. This has since been proven misleading across many sports but this paper, and a need for a systematic approach to youth development, would be the catalyst for the emergence of LTAD models. The most cited milestone in LTAD timelines was Balyi & Hamilton’s model of LTAD in 2004. In this, they highlighted the importance of Peak Height Velocity in a child’s development and illustrated the differences between boys and girls. They also formulated the idea of “windows of opportunity” for physical development and demonstrated a 6 staged approach to late specialised sports.

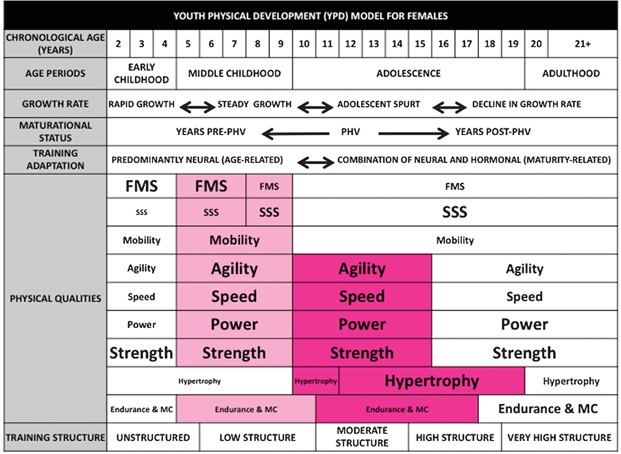

In 2012, Lloyd and Oliver released a paper called “A new approach to long-term athletic development”, claiming that there was no scientific evidence for windows of opportunity and that all components of physical development can be trained all the time. However, the authors gave reference that certain modes of training would be more effective at certain times of the child’s developing years. For example, hypertrophy training would be more effective at post-puberty versus pre-puberty, taking advantage of natural hormonal changes. Noticeably, the model integrated the importance of PHV, from Bayli and Hamilton’s work. It added to Bayli’s breakdown of physical qualities which were 5, into now 9 different entities. The stages of training emphasis evolved into a more training structure format. Finally, the authors referred to the importance of having appropriately trained coaches at this specialised time in a child’s development.

These two models in particular have led to the creation of an array of LTAD models. The existence of LTAD models is now across countries and across sports. It has been applied by national governing bodies and practitioners, for the development of children into elite athletes – England and Wales Cricket Board created theirs in 2005, British Gymnastics in 2006, IRFU in 2006, Canadian Basketball in 2008 to name but a few.

Building Blocks of LTAD

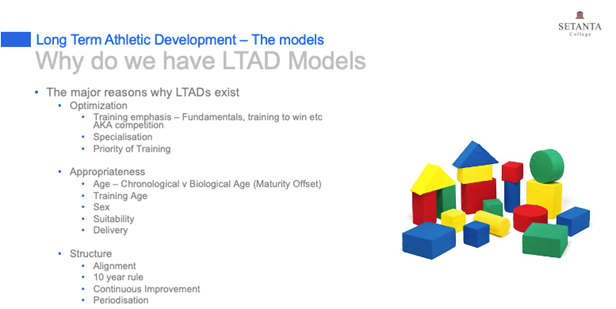

From my own experience in youth development, I have categorized the existence of LTAD’s into 3 critical features or building blocks. I believe the components and the factors within it make up LTAD models. I developed these 3 building blocks to help understand and digest all the moving parts of LTAD. This is my own developed theory and by no means do I suggest you should use them. I do however hope it provides a logical way to systemize a complex concept.

- Optimisation

- Appropriateness

- Structure

Optimisation

“The action of making the best or most effective use of a situation or resource.”

The components of Optimisation:

Training Emphasis

This component reflects the emphasis of the sessions that are delivered on the pitch, in the gym or on the court. The biggest driver in training emphasis or training structure is competition. Competition, and how it’s dealt with, truly denotes whether a phase is “training to win” or “learning to train”. The phases or training emphasis are important and how they formulate within an organization will vary. However, it is competition that transfers what is written on a piece of paper to what is delivered on the ground floor. If competition is introduced too early and given merit, the phases or training emphasis becomes very mucky. For example, if a phase or training emphasis is about “learning to train” but there is a tournament in the same phase which is about winning, and decisions are made based on winning, then the phase is not “learning to train”. So, this is what is meant by “what is written down and what is done is dictated to by competition.”

Specialisation

Early specialization has shown to be detrimental to long-term success. However, to reach a high level in sport, early engagement is necessary. To balance these conflicting theories, Manchester City FC and Arsenal FC have adapted a multi-sport program for the younger ages. There are many benefits to the athlete by providing a more balance development plan, particularly in developing years.

Priority of Training

This incorporates energy system and physical quality development. The development of power, strength, aerobic capacity, etc. all fit under priority of training. In LTAD, prioritising training requires factoring in the athlete’s biological age, sex, training age, injuries, and capabilities but also their sport.

Appropriateness

“The quality of being suitable or proper in the circumstances”

The components of appropriateness:

Age

There are differences between chronological vs. biological age, and both need to be factored into an appropriate LTAD model.

Training Age

This typically represents the amount of years a person has been full time training and can widely vary amongst age groups.

Sex

There are differences both physiologically and biomechanically in males and females. Injury statistics alone indicate that sex should be factored into the type of training being delivered.

Suitability

All sessions across LTAD should be suitable to the athlete you are dealing with. From a coaching perspective, this is about leaving your ego outside and dealing with the bigger picture. I understand all athletes like to be quick even at a young age. However, when you decide to implement sprinting protocols or heavy lifting strategies to athletes, there must be a level of suitability. Teaching the fundamentals of movement should supersede the longing for outcome measures. Implementing a suitable program means the athletes are building for the future.

Delivery

A program can look similar across U12 to U16 even when you consider all the factors. The difference is explained in the delivery. How an under U12 receives his/her program needs to look and feel different to a similar session delivered to an U16.

Structure

“The arrangement of and relations between the parts or elements of something complex.”

The components of Structure:

Alignment

An athlete/player will typically have a few key stakeholders that contribute to their development:

- Parents/Guardian

- Coach

- Agent

- Support Staff

Even in this unexhaustive list, alignment plays a huge role in making sure decisions are made for the right reason. LTAD models provide a source of alignment for the key stakeholders. It helps stakeholders understand that decisions need to be made with a long-term goal in mind. Alignment provides clarity. From my experience, this is important for an athlete to have a quiet and focused mind. Especially with today’s coherent of millennials and Gen Z, there appears to be a rush to success and there is an unhappiness with process. LTAD can be extremely useful to shape the mindset of young athletes, by illustrating that they are on a progressive journey and every step they take brings them closer to the ultimate goal.

The 10 Year Rule

This is a contentious issue, but there is no doubt that time and deliberate practise is needed to attain expert level performances. The 10,000 hour is likely inaccurate and quite misleading, but athletes need to invest a significant portion of their lives if they want to reach high levels of performance. Long-term, structured programmes will provide a higher probability of success if the relevant factors are considered.

Continuous Improvement

Continuous improvement is something we are all chasing. Continuous improvement is not something that just happens. The key to it is consistency of practice. If you want to be good or get better at something, there needs to be consistency and frequency. Structure allows consistency of practice and frequency to exist which in turn induces continuous improvement.

Periodisation

Periodisation is the process of dividing an annual training plan into specific time blocks. The foundations of periodisation are built on three cycles: Marco, Meso and Micro. The premise of periodisation is to allow principles of training to occur – in particular overload and recovery. Different energy systems or physical qualities can be trained and overloaded to drive enhanced adaptation. Without an appropriate structure, athletes can get injured, burnout and “fall out of love” with their sport.

Bayli & Hamliton’s (2004) LTAD Model with the 3 building blocks indicated.

LTAD is a sound conceptual model for the management of youth development but should not be seen as literal or prescriptive. Many of the concepts are not based on conclusive evidence. Therefore, we should not hold ourselves accountable to a 1-dimensional model. LTAD models do however provide a framework to manage complex matters in complex organisations, for example, professional football academies. They provide guidelines and direction but should never be used without context. It must be understood that sporting success is multi-factorial and LTAD models don’t always recognise the sport or the innate/genetic contributions to the sport. The amount of training hours or deliberate practice is not a differentiating factor for elite success (Gullich 2016). In addition, early exposure is likely to be crucial for expert performance, but delayed specialisation improves the chances of adult success (Moesch et al, 2011).

Coaching is often seen as a mixture of science and art. LTAD models should be seen similar to that. There are principles that need to be adhered to but often there is intuition or experience to be called upon for these models to be implemented correctly, into the environment and the context.

To learn more about the courses offered by Setanta College, you can contact us here or download our brochure below.

Download Course Brochure

References

- Ericsson, K. & Krampe, R. (1993) The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychology Review, 100, 363–406.

- Güllich A. Many roads lead to Rome – developmental paths to Olympic gold in men’s field hockey. Eur J Sport Sci 2014;14:763–71.

- Moesch, K., Elbe, A-M., Hauge, M-L.T., Wikman, J.M.(2011) Late specialization: the key to success in centimetres, grams, or seconds (cgs) sports. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science Sports, 21(6) 282–290.

- Güllich, A., Kovar, P., Zart, S., & Reimann, A. (2016). Sporting activities leading to higher or lower improvement of match-play performance in elite youth soccer – a 2-year longitudinal study. Journal of Sports Sciences, 34.

- Güllich, A., & Emrich, E. (2014). Considering long-term sustainability in the development of world class success. European Journal of Sport Science, 14(S1), 383–397

- Hornig, M., Aust, F., & Güllich, A. (2016). Practice and play in the develop- ment of German top-level professional football players. European Journal of Sport Science, 16, 96–105

- Balyi, I. & Hamilton, A.(2004) Long-Term Athlete Development: Trainability in Childhood and Adolescence—Windows of Opportunity—Optimal Trainability. Victoria, Canada: National Coaching Institute British Columbia & Advanced Training and Performance Ltd, 2004.

- Rhodri, L. & Oliver, J. (2012The Youth Physical Development Model: A New Approach to Long-Term Athletic Development, Strength and Conditioning Journal, 34 (3), 61-72

Leave A Comment